Practice point

Care for children and youth with cerebral palsy (GMFCS levels III to V)

Posted: Sep 29, 2023

Principal author(s)

Scott McLeod, MD, FRCPC; Amber Makino, MD, FRCPC; Anne Kawamura, MD, FRCPC, Developmental Paediatrics Section

Abstract

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common physical disability in Canadian children. The comprehensive care of ambulatory children with CP functioning at Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level I and II was covered in a previous practice point. This companion document focuses on the care of children with CP functioning at GMFCS levels III to V. Children functioning at GMFCS level III and IV mobilize using devices such as a walker, canes, or powered mobility, while those functioning at GMFCS level V require assisted mobility, such as a manual wheelchair. An overview of key concepts in early detection, rehabilitation services, and therapeutic options for children with CP at these levels is provided, along with practical resources to assist health surveillance for paediatricians caring for this population.

Keywords: Anticipatory guidance; Cerebral palsy; Early detection; Surveillance

Early diagnosis and motor prognostication

An accurate diagnosis of cerebral palsy (CP) is often possible to make in infants, based on a combination of findings from a physical examination tool (e.g., notably the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE)) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[1]. CP subtype and future ambulation status can also be predicted[1] on this basis. At-risk newborns, such as those born preterm or with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, should receive close monitoring as part of their neonatal follow-up program. For these at-risk infants, a CP diagnosis can be predicted accurately before 6 months based on a motor function assessment (e.g., Prechtl’s General Movement Assessment) combined with HINE and MRI findings[1].

Guidelines recommend early intervention with task-specific motor training for infants with (or at high risk for) CP, to harness neuroplasticity and improve long-term motor and cognitive outcomes[2]. Early detection and prompt referral for intervention services will support caregiver well-being[1]. Whenever possible, interventions should occur in a natural environment, like the child’s home, and with caregiver assistance, such that therapies can be tailored to meet infant tolerance, needs, and family-centred goals[1].

When a diagnosis is made, parents often ask paediatricians about future skills. By age 2, a gross motor trajectory can be established and the GMFCS is helpful for predicting motor outcomes[3]. It is rare for individuals to move more than one level up or down on the GFMCS[4], and most of a child’s motor development has been achieved by 5 years of age[5]. Despite these facts, paediatricians should continue to encourage children with CP to develop independent adapted mobility, and promote lifelong participation in motor activities throughout life[5].

For all prognostic conversations, maintaining a strengths-based approach and focusing on a child’s independence and abilities (rather than what they cannot do) are important. Use positive phrasing. For example, “We’re going to focus on helping your child to move independently, which may include an assistive device, like a walker”, or “Encouraging kids to explore the world and move when and where they want to—as independently as possible—is really important for their overall development”, will be more positively received than “Your child won’t be able to walk independently”. Providing hope and an optimistic outlook, while managing parental expectations, is crucial for maintaining relationships with families and supporting them throughout their child’s journey.

The developmental and rehabilitative ‘home’

Paediatricians are important contacts for children, youth, and families seeking advice on therapeutic options for CP. Practical resources like the ‘State of the evidence traffic lights’, which is a continually updated and comprehensive review of interventions for CP, can help paediatricians become familiar with (and stay abreast of) therapeutic options. The tool provides visual level of evidence indicators for a range of options, using a ‘bubble chart’[6].

Current paediatric rehabilitation approaches promote the early initiation of ‘child-active’, goal-directed therapies[7], rather than more ‘child-passive’ strategies (i.e., which are “done to” the child), which aim to normalize movement through non-specific motor stimulation. Therapy goals focus on active practice of real-life tasks (e.g., walking with a walker, riding an adapted bicycle, feeding with a spoon) that are meaningful for the child and family. The GMFCS can help ensure that goals are linked to functional capabilities. For example, a child functioning at GMFCS level IV may work toward activating a start-up switch on a powered wheelchair, rather than trying to learn to walk. Asking children and caregivers what they like to do for fun can open conversations around adapting activities to promote participation and physical fitness (e.g., sledge hockey, Track 3 skiing, adapted bicycling). Recreational therapists can help find and connect families with socially stimulating recreation activities that are enjoyable for the child, provide respite for parents, and encourage community engagement. Programming varies widely depending on location, such that conversations and connection will depend on local opportunities.

Communication is an essential skill for all children. Some children with CP have dysarthria, which makes oral communication difficult. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods can maximize ability to communicate, thereby supporting inclusion, socialization, and learning. Specialized consultation is required to find methods that best ‘fit’ each child, which can depend on factors such as manual dexterity, cognition, and vision. Options range from teaching signing or using pictures in an assistive book, to a speech-generating device or eye gaze technology that can be mounted on mobility devices to enable access wherever the child goes.

Psychoeducational assessments are essential to ensure that child care, school, and other learning environments are adapted to support an individual child’s strengths and needs. Because funding is often limited for such assessments, communication and consultation between the school and a child psychologist may be needed to determine appropriate assessment timing for a child’s age and stage.

Supportive equipment

Because hip subluxation is common in children functioning at GMFCS levels III to V, access to standing frames to promote weight-bearing activity is important. Ankle-foot orthoses, knee-extension splints, and hand-resting splints help prevent muscle contractures that can impair comfort and daily function. To prevent falls, maximize accessibility, and increase independence and ease of care, assistive furniture or equipment such as safety railings, bath chairs, or shower benches, and ramps and lifts can be used at home. Such adaptations can also ease the caregiver burden. Referral to an occupational therapist for a home safety and equipment review can be invaluable.

Health surveillance

Having a consistent ‘medical home’ for children and youth with CP helps build and strengthen long-term relationships among paediatric primary care providers, the young people they see, and families. For any family, interpersonal relationships, family function, and family well-being can be harder to maintain during life transitions and times of stress. Exploring and addressing the social determinants of health with each family who are living with inequities, and helping them to navigate systems, access counselling, or obtain respite care and other services, can profoundly impact child and family well-being.

Rehabilitation strategies are the cornerstone for managing CP, but when hypertonia causes pain, impacts care (e.g., dressing or hygiene), or limits participation, further treatment is required. A personalized referral to a rehabilitation centre or therapist with experience in hypertonia may be needed. Oral medications that have a generalized effect of reducing muscle tone are commonly used. Oral baclofen is a first-line treatment for generalized spasticity and dystonia in children with CP. Common side effects include constipation and sedation. Families should be cautioned against stopping baclofen abruptly because it can lead to rebound hypertonia. When focal hypertonia (i.e., in specific muscles or muscle groups) is causing pain, interfering with caregiving, or affecting function, periodic injections of botulinum toxin A may be considered. An evidence-based care pathway to assist clinicians treating dystonia in children with CP is available online.

Taking a systematic approach to health surveillance can help children with CP, GMFCS levels III to V (Figure 1). Evidence-based care pathways that aid clinician surveillance and treatment for hip subluxation, osteoporosis, and sialorrhea have been established as effective. Monitoring for hip subluxation based on physical exam and an anterior-posterior (AP) pelvis x-ray should generally occur every 6 to 12 months for this population, because children with CP are at increased risk. Identifying hip migration early in children who do less weight-bearing (i.e., GMFCS levels III to V) can facilitate timely orthopedic interventions[8]. Referral to orthopedics is typically recommended when imaging shows that >30% of the femoral head is uncovered by the pelvis, because soft tissue releases or hip reconstructive surgery may be required to prevent hip dislocation and chronic pain[8].

Promoting bone health with regular vitamin D supplements, ensuring adequate dietary calcium, and regular weight-bearing or supported weight-bearing activities are vital. Regular assessment of nutritional status and swallowing difficulties based on careful history-taking and videofluoroscopic swallowing studies, as needed, can impact counselling on intake and safe feeding. Maintaining an upright position while eating, pacing intake, and thickening liquids can help prevent food aspiration, one of the most common reasons for hospitalization in children with CP.

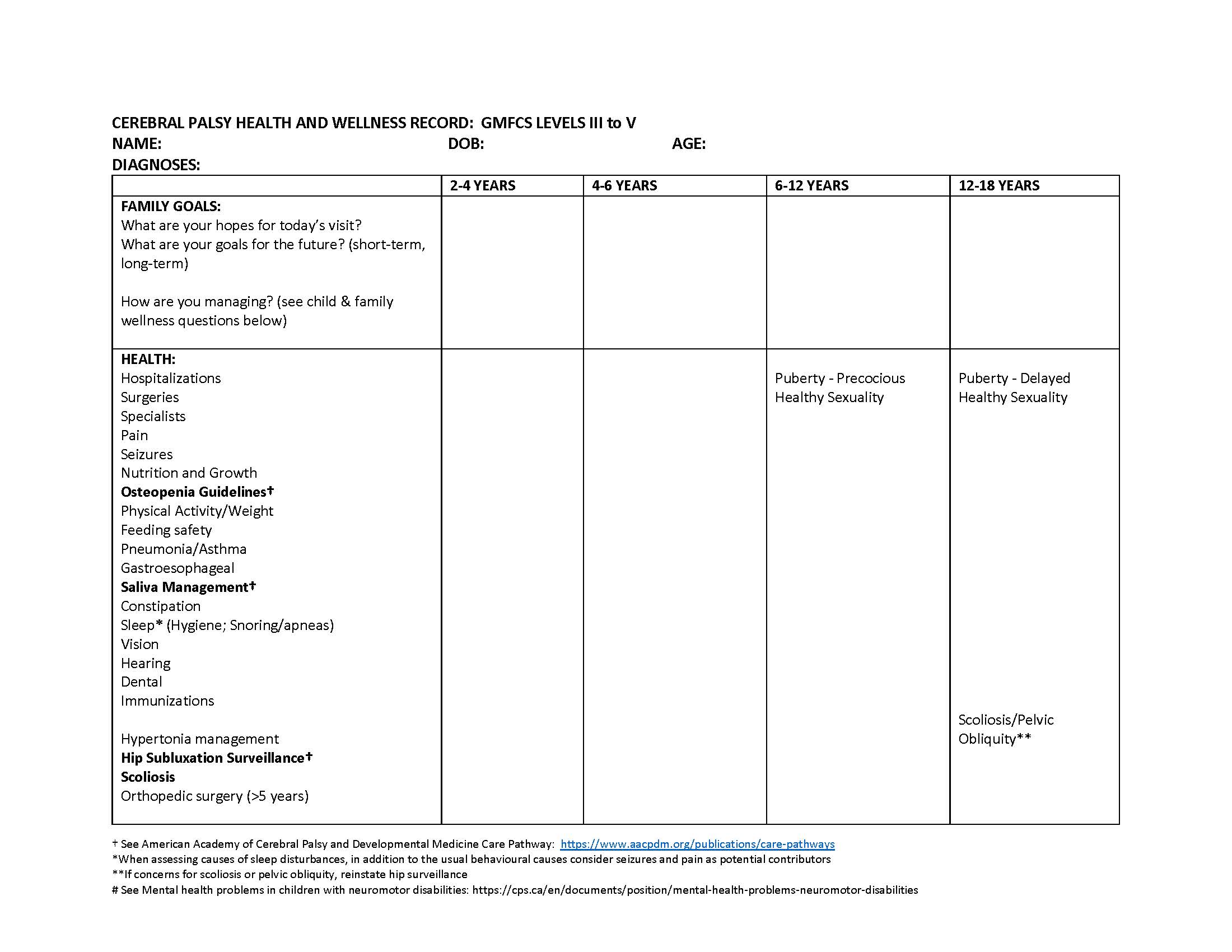

Figure 1. Cerebral palsy health and wellness record for children functioning at GMFCS III to V

This record from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital may be printed and used alongside other evidence-based health promotion guides, such as the Rourke Baby Record and Greig Health Record, to provide clinicians with a framework for exploring relevant areas of care for children with CP functioning at GMFCS III to V.

Surgical options

Neurosurgical options may be considered in situations where first-line treatments have failed and hypertonia continues to affect a child’s functional abilities or quality of life. Because children and youth with CP require specialized management by a multidisciplinary team, referral to a tertiary centre is often required.

Selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR) is a procedure where selected nerve rootlets are severed to modify sensory inputs in the reflex arc, reducing spasticity. Individuals can be considered for SDR if they:

- Were born preterm, with characteristic white matter injuries such as periventricular leukomalacia,

- Do not have a co-occurring dyskinetic movement disorder,

- Do not experience musculoskeletal contracture,

- Possess antigravity muscle strength, or

- Live with positive psychosocial factors (e.g., they can access and participate in a therapy program)[9][10].

Benefits of SDR appear to be greatest in individuals with CP GMFCS levels II and III. While SDR as an option is controversial for children functioning at GMFCS levels IV and V, some children who have had this surgery experienced improvement in gross motor tasks, and have exceeded their expected natural history[9].

Intrathecal baclofen (ITB) treatment involves surgically implanting a reservoir pump and catheter to deliver baclofen to the intrathecal space. ITB can treat dystonia and spasticity in individuals with CP who are functioning at GMFCS levels IV and V[11]. Indications for ITB include failure of oral medications (e.g., baclofen) to treat hypertonia causing pain or interfering with quality of life or activities of daily living [11]. Complication rates are high, and catheter dislodgment or pump malfunction can lead to severe baclofen withdrawal. Individuals treated with ITB must have access to specialized emergency care.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a form of neuromodulation that is reserved for children with severe, refractory dystonia and significant functional impairment despite appropriate medical management and when other treatment options are not possible[12]. Studies to date of DBS in children with CP are small but have shown significant reductions in pain-related symptoms and analgesia requirements[13].

Best practice points

Children and youth with cerebral palsy (CP) GMFCS levels III to V should have a developmental and rehabilitative ‘home’ that provides regular surveillance and monitoring for common health issues and conditions in this population. Paediatricians are ideally situated to follow up, support wellness, and guide children and families living with CP to be as independent and healthy as possible. They also provide a nexus for communication with health team members, school authorities, hospital-based care providers, and community services.

Paediatricians and other primary care providers should endeavour to:

- Support early diagnosis by using evidence-based tools such as the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE) and magnetic resonance imaging to facilitate referrals for timely intervention and access to supportive services.

- Explore goal-directed and active rehabilitation with children and families, with a focus on fun, fitness, and friendship.

- Provide ongoing health surveillance and support by maintaining a comprehensive health and wellness record.

Acknowledgements

This practice point has been reviewed by the Complex Care Section Executive and the Community Paediatrics, and Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY DEVELOPMENTAL PAEDIATRICS SECTION (2021-2022)

Members: Sabrina Eliason MD (President); Alexandra Jackman MD; Jenna McWhirter BSCH, MD (Resident Liaison); Asha Nair MD; Jacqueline Ogilvie MSC, MD, FRCPC; Angela Orsino MD (Secretary-treasurer); Iskra Peltekova MD; Melanie Penner MD (Past-president); Gurpreet (Preety) Salh MD, FRCPC (Vice-president)

Principal authors: Scott McLeod, MD, FRCPC; Amber Makino, MD, FRCPC; Anne Kawamura, MD, FRCPC

References

- Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, et al. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(9):897–907. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1689.

- Morgan C, Fetters L, Adde L, et al. Early intervention for children aged 0 to 2 years with or at high risk of cerebral palsy: international clinical practice guideline based on systematic reviews. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175(8):846–58. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0878.

- Rosenbaum PL, Palisano RJ, Bartlett DJ, Galuppi BE, Russell DJ. Development of the Gross Motor Function Classification System for cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50(4):249–53.

- Palisano RJ, Cameron D, Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Russell D. Stability of the gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48(6):424–8. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000934.

- Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Hanna SE, et al. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: Creation of motor development curves. JAMA 2002;288(11):1357–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1357.

- Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2020;20(2):3. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z.

- Novak I. Evidence-based diagnosis, health care, and rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol 2014;29(8):1141–56. doi: 10.1177/0883073814535503.

- American Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine. Hip Surveillance in Cerebral Palsy. 2017. https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/hip-surveillance-in-cerebral-palsy (Accessed March 31, 2023).

- Iorio-Morin C, Yap R, Dudley RWR, et al. Selective dorsal root rhizotomy for spastic cerebral palsy: A longitudinal case-control analysis of functional outcome. Neurosurgery 2020;87(2):186–92. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz422.

- Summers J, Coker B, Eddy S, et al. Selective dorsal rhizotomy in ambulant children with cerebral palsy: An observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3(7):455–62. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30119-1.

- Bonouvrié LA, Becher JG, Vles JSH, Vermeulen RJ, Buizer AI; IDYS Study Group. The effect of intrathecal baclofen in dyskinetic cerebral palsy: The IDYS Trial. Ann Neurol 2019;86(1):79–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.25498.

- Sanger TD. Deep brain stimulation for cerebral palsy: Where are we now? Dev Med Child Neurol 2020;62(1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14295

- Perides S, Lin JP, Lee G, et al. Deep brain stimulation reduces pain in children with dystonia, including in dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020;62(8):917–25. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14555.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Last updated: Feb 15, 2024